And I love that way of showing us a new environment: Just letting it happen naturally while the story unfolds, and keeps us (the readers) on our toes.

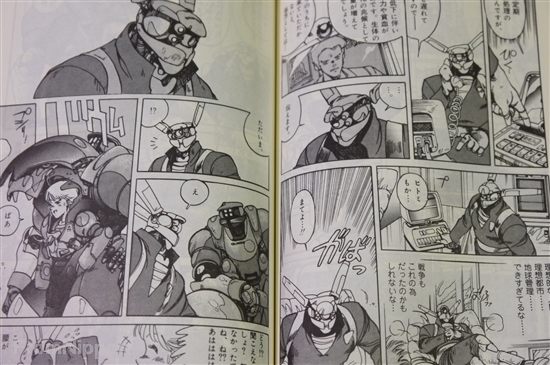

It’s not until many many pages later that we find out for sure that he is a cyborg with both organic and metal parts. Like since if they’re talking about dinner, then that robot guy perhaps isn’t a robot anyway? Or something: Shirow doesn’t tell us what’s going on, but just drops us into the world and allows us to make the connections. The page above is part of the sequence where we’re introduced to the main characters, who initially appear to be a plucky, young, housewife with a helpful robot husband. There’s so much world-building behind the things that Shirow shows us. (Note the mirror Earth above because Eclipse forgot to flip the panel after flopping the page.)īut it’s not an unwarranted prize. In addition, Masamune Shirow is a pseudonym, so there’s that sense of intrigue which might have helped with his success in Japan (he won the “Best Graphic Novel” prize at a Japanese science fiction festival for the first Appleseed book. Shirow, as opposed to most other successful comics artists in Japan, didn’t employ an entire studio of “assistants” (i.e., people who do most of the work), but instead (apparently) did everything himself, while holding down a day job as a teacher.

I’m just foreshadowing what’s coming in this blog article near the end.īut first we’ll talk about Masamune Shirow’s Appleseed. He was running Studio Proteus as a packager of Japanese comics for the US market, and most of these were published through Eclipse. Viz pulled out of the deal because they didn’t feel that Eclipse were able to sell sufficient quantities of comics, so Eclipse turned to Toren Smith instead. Appleseed (1988) #1-19 by Masamune Shirow.Īll the previous translations of Japanese comics published by Eclipse had been provided (and picked) by Viz Comics.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)